Moving and editing

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How can I edit files on my HPC

How can I change file permissions?

How can I transfer files from a HPC

Objectives

Learn how to navigate around a remote system

Utilise navigational Linux commands

Understand and manipulate UNIX permissions

Utilise the

vimtext editor tool

Using text editors

In the previous episode, we saw a reference to text editors, namely vim and

nano

Getting used to text editors

Spend 10 minutes getting used to working with

vimornano

Command Action iEnter into INSERT mode, which will allow you to write text EscEnters into COMMAND mode, where commands like the below can be written :wqWrites, saves and exits the file :q!Force quits without saving

nanohas all the commands in the editor window.

File permissions

All files have owners. There is yourself, the machine user, a group owner, which is a group on a machine and then others.

Once you are on a machine and have multiple people on the same machine, it is important to know that others can access your files. By default, you, the machine user and write and edit a file, but everyone else will have read-only privileges. Let’s see what this looks like.

$ ls - lh hamlet.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 user staff 193K 11 Jan 12:00 hamlet.txt

The -h flag puts our output into human-readable format, so the size of our file is expressed in kilobytes. The main

area of interest for us though is on the left.

The first - may sometimes be filled with d, standing for directory, however our interest area are the 9 characters

to the right, which is divided into three sections, user, group and other.

The first section above has the three characters rw-, which indicates that the user can read and write content to the

file. The permission can be changed so that the file can be executed or run, however we will come to that shortly.

The second section r-- refers to the group owner, i.e. a group on a machine. Here the w has been replaced with a

- indicating that the group has read-only permissions. This is a similar case for the third section, also r--,

which indicates that others have read-only permissions.

Who cares you may ask. Well, a common occurrence is that people on a project or a course would need to share and edit files,or need to access materials from a directory outside of their account. As things stand, this is not possible, but by changing permissions, this is possible.

We can change the permissions of a file using chmod along with a variety of flags which can add or take away file

permissions. Let’s change the permissions of our correct.txt, then use echo to write to the file.

$ chmod u-w correct.txt

$ echo "new line" > correct.txt

permission denied: correct.txt

As you can see, because we have changed permissions, we cannot edit the file anymore.

Let us change the permissions, but add writing permissions to all users (user, group, other)

$ chmod ugo+w correct.txt

Now when we check the permissions with ls -lh we can see that the permissions have changed to;

-rw-rw-rw-

Changing file permissions

You may need to change the permissions of a file so group users can edit, or execute the file.

Create a new file,

my_script.sh, which should automatically have the permissions-rw-r--r--. Check yourself that the file has these permissions, then;

- Add executable permissions for user and group

- Remove reading permissions for other

Solution

$ chmod ug+x my_script.sh $ chmod o-r my_script.sh

There are also number notations corresponding to u, g and o read, write and executable permissions, as shown in

the table below.

| Character | Number Notation | Character | Number Notation |

|---|---|---|---|

--- |

0 | r-- |

4 |

--x |

1 | r-x |

5 |

-w- |

2 | rw- |

6 |

-wx |

3 | rwx |

7 |

These numbers are read in as a three character long binary number, read from right to left. The below example shows how the numbers can be summed up, so that;

- The owner can read, write and execute the file

- The group can read and execute the file, but not edit it

- All others cannot read, write or execute it

OWNER GROUP OTHER

r w x r w x r w x

1 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0

7 5 0

|______|______|

|

750

If we wanted to change a file’s permissions to match the above, we can do so using;

$ chmod 750 my_script.sh

Who has what permissions?

Have a look at the different

rwxpermissions and numerical equivalents, and deduce who has what permissions, or who has been granted, or had permissions retracted

rwxrwxr--r--r--r--755700rwxrw-r--chmod u+x filechmod go-wx fileSolution

- User and group can read, write, execute. Other can only read the file.

- User, group and other can only read the file

- User can read, write and execute the file. Group and other can read and write the file.

- User can read, write and execute the file, group and other cannot do anything.

- User can read, write and execute the file. Group can read and write the file. Other can read the file.

- The user has been given permission to execute the file.

- Group and other has has permissions to read and write the file retracted.

File transfer with scp

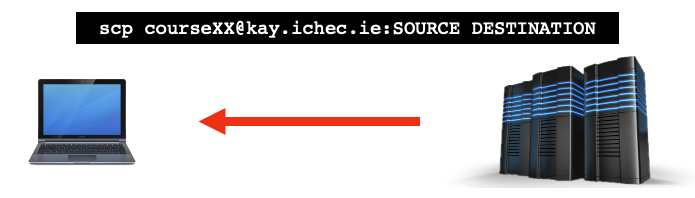

So, you’ve created a file or group of files on your account, now how can you copy them onto your local machine?

To do this we need to remind ourselves of the difference between your local machine and the remote host. This is

always outlined in the prompt, so recognising the information in the prompt is very important. Let us take a

simplified example of the Earth and a satellite. The Earth, or specifically a specific “address” on the Earth is

the local machine, let us say it has the address 0123-laptop. The satellite is the remote host, the machine

that you are connecting to, let us say it has the address satellite.world. For each of these machines, you have a

username, and they may be different depending on the machine, but for simplicity here we will use the same username,

johnsmith. The prompts for the local and remote machines would therefore be as follows;

- Local:

johnsmith@0123-laptop - Remote:

johnsmith@satellite.world

Let’s have a quick think first.

Transferring files… “where” is important!

Say that you are have some files on the satellite and you want to take them off the satellite and onto your local machine. Where would you need to run the command to transfer files from?

Solution

Your local machine.

Whether you were right or wrong, take a moment to think about why.

You may have been a bit stumped by that, because surely as we are working on a remote host, be it a supercomputer or

satellite, that should be where the command is run from, but it is not. Let’s take the situational approach, and

imagine you are working on the satellite in the directory johnsmith@satellite.world:~/files/, with a files present

there called mydata.dat. You now want to transfer it to a directory your local machine, the address and directory

that you want to send it to being johnsmith@0123-laptop:~/localdata/. There is a big problem here, as the satellite

has no idea where 0123-laptop is!

Laptop/local addresses are typically very vague without much context, but that is not the reason. You can connect from a local host to a remote host but not the other way around. Therefore the local host has to fetch material from the remote host.

Therefore, we need to take note of the path to our file on the remote host, ~/files/myfile.txt. From there, we need

to open a terminal on our local machine and utilise a new command, scp, which stands for secure copy. From there,

it operates in a very similar way to the cp command.

On your local machine, the syntax is as follows;

$ scp johnsmith@satellite.world:~/files/myfile.txt /path/to/directory

You may well need to enter the passwords that you needed to access the remote machine. A useful tip to make the command

more manageable, is to navigate to the directory that you want to put the files on your local machine, and use the

current directory notation (.) in the following manner.

$ scp johnsmith@satellite.world:~/files/myfile.txt .

This places the file into your current directory, and can be a handy way to make the command less complicated for starters!

Often, we don’t just transfer one file at a time, we may want to transfer entire directories, which we do by using the

recursive flag (-r) as shown below.

$ scp -r johnsmith@satellite.world:~/files .

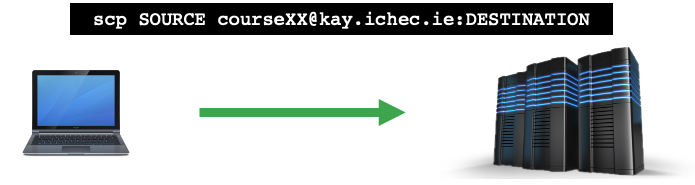

If you want to get something from your local machine onto a remote host, then the command will naturally be a bit different, as the file to be transferred needs to go first, followed by the directory to put it into on the remote host. It is once again recommended to navigate to the local file and confirm the directory on the remote host.

$ scp localfile.txt johnsmith@satellite.world:~/files/

scpfiles onto your local machineUse

scpto undertake the following steps

- Create a directory on the remote host and create some empty files.

- Use

scpto transfer a single one of those files to a directory on your local machine.- Repeat but use the recursive option to copy the entire folder to your local machine.

- On your local machine, edit the file you have copied, and add another file into the directory you have transferred.

scpyour edited files and directory back onto the remote host.

Common problems that can be encountered with this include running the command on the remote host rather than the local machine. So be careful to keep that in mind. Some terminal emulators, such as Cygwin do not have the option to use two terminal windows simultaneously can be tricky. We recommend therefore taking a note of the directory where your file is stored on the supercomputer before attempting.

SCP/SFTP clients

There are plenty of software packages out there that can utilise SCP, and not all of them need to be based in the terminal. The main clients (some of which have terminal emulators) include, but are not limited to;

- MobaXterm

- Git Bash

- Filezilla

- Bitvise

- WinSCP

- Cyberduck

That being said however, the terminal option is preferable in place of having another software package on your machine.

Key Points

You will have 2 main directories associated with your account. Your

workdirectory will have much more space thanhomeAbsolute path is the location in a file system relative to the root

/directoryRelative path is the location in a file system relative to the directory you are currently in

vimis one of the most popular and flexible text editors