Cython

Overview

Teaching: 45 min

Exercises: 60 minQuestions

What is Cython?

What’s happening under the hood?

How can I implement a Cython workflow?

How can I create C-type declarations?

Objectives

To understand the main concepts of C relative to Cython

Learn how to implement a Cython workflow in a Jupyter notebook and in a terminal environment]9oii

Implement type declarations across variables and functions, as well as compiler directives

Undertake a Julia-set example

What is Cython?

Cython is a programming language that makes writing C extensions for the Python language as easy as Python itself. The source code gets translated into optimised C/C++ code and compiled as Python extension modules. The code is executed in the CPython runtime environment, but at the speed of compiled C with the ability to call directly into C libraries, whilst keeping the original interface of the Python source code.

This enables Cython’s two major use cases:

- Extending the CPython interpreter with fast binary modules

- Interfacing Python code with external C libraries

An important thing to remember is that Cython IS Python, only with C data types, so lets take a little but of time to get into some datatypes.

Typing

Cython supports static type declarations, thereby turning readable Python code into plain C performance. There are two main recognised ways of “typing”.

Static Typing

Type checking is performed during compile-time. For example, the expression x = 4 + 'e' would not compile. This

method of typing can detect type errors in rarely used code paths

Dynamic Typing

In contrast, type checking is performed during run-time. Here, the expression x = 4 + 'e' would result in a runtime

type error. This allows for fast program execution and tight integration with external C libraries.

Datatype declarations

Python is a programming language with an exception to the normal rule of datatype declaration. Across most programming languages you will see variables associated with a specific type, such as integers (

int), floats (float,double), and strings (str).We see datatypes used in pure Python when declaring things as a

listordict. For most Cython operations we will be doing the same for all variable types.

Implementing Cython

This can be implemetned either by Cython scripts or by using cell magics (%%) in Jupyter notebooks. Although the

notebooks are available, we also recommend trying these methods outside the notebook, as it is the more commonly used

implementation. You can use Jupyter notebooks to create external files as an alternative.

Using Jupyter Notebook cell magics with Cython

As discussed in episode 2, we can use cell magics to implement Cython in Jupyter notebooks. The first cell magic that we need is to load Cython itself. This can be done with a separate cell block that only needs to be run once in the notebook.

%load_ext cythonFrom there, any cell that we wish to “cythonise” needs to have the following on the first line of any cell.

%%cython # Some stuff

Let’s look at how to cythonise a simple function which calculates the Fibonacci sequence for a given set of numbers,

n. Below we have the python code for a file which we have named fibonacci.py.

def fib(n):

# Prints the Fibonacci series up to n.

a, b = 0, 1

while b < n:

print(b)

a, b = b, a + b

Although we are only dealing with one file here, it is common practice to have a “main” file from which all other files

and functions are called. This may seem unnecessary for this simple setup, but is good practice, particularly when you

have a setup that has dozens, hundreds of functions. We will create a simple fibonacci_main.py file which imports the

fib function, then runs it with a fixed value for n.

from fibonacci import fib

fib(10)

From here we can run the file in the terminal, or if you are using Jupyter notebook, you can use the cells themselves,

or use the ! operator to implement bash in the codeblock.

$ python fibonacci_main.py

That’s our Python setup, now let’s go about cythonising it. We will use the same function as before, but now we will

save it as a .pyx file. It can be helpful when dealing with Cython to rename your functions accordingly, as we can

see below.

def fib_cyt(n):

# Prints the Fibonacci series up to n.

a, b = 0, 1

while b < n:

print(b)

a, b = b, a + b

Before we change our fibonacci_main.py to implement the function using Cython, we need to ado a few more things.

This .pyx file is compiled by Cython into a .c file, which itself is then compiled by a C compiler to a .so or

.dylib file. We will learn a bit more about these different file types in the

next episode.

There are a few different ways to build your extension module. We are going to look at a method which creates a file

which we will call setup_fib.py, which “cythonises” the file. It can be viewed as the Makefile of python. In it, we

need to import some modules and call a function which enables us to setup the file.

from distutils.core import setup, Extension

from Cython.Build import cythonize

setup(ext_modules = cythonize("fibonacci_cyt.pyx"))

Let us have a look at the contents of our current working directory, and see how it changes as we run this setup file.

$ ls

04-Cython.ipynb exercise fibonacci_cyt.pyx setup_fib.py

__pycache__ fibonacci.py fibonacci_main.py

At this stage all we have are our original Python files, our .pyx file and setup_fib.py. Now lets run our

setup_fib.py and see how that changes.

In the terminal (or by using ! in notebook), we will now build the extension to use in the current working directory.

You should get a printed message to the screen, now let’s check the output of ls to see how our directory has changed.

04-Cython.ipynb fibonacci_cyt.c

__pycache__ fibonacci_cyt.cpython-38-darwin.so

build fibonacci_cyt.pyx

exercise fibonacci_main.py

fibonacci.py setup_fib.py

So, a few more things have been added now.

- The

.cfile, which is then compiled using a C compiler - The

build/directory, which contains the.ofile generated by the compiler - The

.soor.dylibfile. This is the compiled library

Next we add the main file which we will use to run our program. We can call it fibonacci_cyt_main.py.

from fibonacci_cyt import fib_cyt

fib_cyt(10)

Upon running it, you can see that it works the same as our regular version. We will get into ways on how to speed up the code itself shortly.

Compiling an addition module

Define a simple addition module below, which containing the following function, and write it to a file called

cython_addition.pyx.Modify it to return x + y.def addition(x, y): # TODOUtilise the function by importing it into a new file,

addition_main.py. Edit thesetup.pyaccordingly to import the correct file. Use the demo above as a reference.Solution

cython_addition.pyxdef addition(x, y): print(x + y)

addition_main.pyfrom cython_addition import addition addition(2,3)

setup.pyfrom distutils.core import setup, Extension from Cython.Build import cythonize setup(ext_modules = cythonize("cython_addition.pyx"))$ python setup.py build_ext --inplace $ python addition_main.py

Accelerating Cython

Compiling with Cython is fine, but it doesn’t speed up our code to actually make a significant difference. We need to implement the C-features that Cython was designed for. Let’s take the code block below as an example of some code to speed up.

import time

from random import random

def pi_montecarlo(n=1000):

'''Calculate PI using Monte Carlo method'''

in_circle = 0

for i in range(n):

x, y = random(), random()

if x ** 2 + y ** 2 <= 1.0:

in_circle += 1

return 4.0 * in_circle / n

N = 100000000

t0 = time.time()

pi_approx = pi_montecarlo(N)

t_python = time.time() - t0

print("Pi Estimate:", pi_approx)

print("Time Taken", t_python)

Running this as a .py file for 100,000,000 points will result in a time of ~27.98 seconds. Compiling with Cython

will speed it up to ~17.20 seconds.

It may be a speed-up but not as significant as we would want. There are a number of different methods we can use.

Static type declarations

These allow Cython to step out of the dynamic nature of the Python code and generate simpler and faster C code, and sometimes it can make code faster by orders of magnitude.

This is often the simplest and quickest way to achieve significant speedup, but trade-off is that the code can become more verbose and less readable.

Types are declared with cdef keyword. Now let’s implement this into our montecarlo file.

def pi_montecarlo(int n=1000):

cdef int in_circle = 0, i

cdef double x, y

for i in range(n):

x, y = random(), random()

if x ** 2 + y ** 2 <= 1.0:

in_circle += 1

return 4.0 * in_circle / n

Running this using the timing setup from the previous code block, by only declaring our variables as an int and

double has decreased our execution time to ~4.03 seconds.

We can go further though!

Typing function calls

As with ‘typing’ variables, you can also ‘type’ functions. Function calls in Python can be expensive, and can be even more expensive in Cython as one might need to convert to and from Python objects to do the call.

There are two ways in which to declare C-style functions in Cython;

- Declaring a C-type function with

cdef. This is the same as declaring a variable - Creating a Python wrapper with

cpdef

Using

cdefandcpdefin notebooks with magicsA side-effect of

cdefis that the function is no longer available from Python-space, so Python won’t know how to call it.If we declare a simple function like below in a Jupyter notebook cell;

cdef double cube_cdef(double x): return x ** 3And from there we use

%time cube_cdef(3), we will get the following error.--------------------------------------------------------------------------- NameError Traceback (most recent call last) <timed eval> in <module> NameError: name 'cube_cdef' is not definedIf we want to be able to use the magics command, we will need to use

cpdef.

Now let’s implement our function call.

cdef double pi_montecarlo(int n=1000):

'''Calculate PI using Monte Carlo method'''

cdef int in_circle = 0, i

cdef double x, y

for i in range(n):

x, y = random(), random()

if x ** 2 + y ** 2 <= 1.0:

in_circle += 1

return 4.0 * in_circle / n

Our timing has reduced again to ~3.60 seconds. Not a massive decrease, but still significant.

Static type declarations and function call overheads can significantly reduce runtime, however there are additional things you can do to significantly speed up runtime.

NumPy arrays with Cython

Let’s take a new example with a numpy array that calculates a 2D array.

import numpy as np

def powers_array(N, M):

data = np.arange(M).reshape(N,N)

for i in range(N):

for j in range(N):

data[i,j] = i**j

return(data[2])

%time powers_array(15, 225)

CPU times: user 159 µs, sys: 112 µs, total: 271 µs

Wall time: 294 µs

array([ 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256,

512, 1024, 2048, 4096, 8192, 16384])

A small function that takes a short amount of time, but there is a NumPy array we can cythonise. We need to import

NumPy with cimport then declare it as a C variable.

import numpy as np # Normal NumPy import

cimport numpy as cnp # Import for NumPY C-API

def powers_array_cy(int N, int M): # declarations can be made only in function scope

cdef cnp.ndarray[cnp.int_t, ndim=2] data

data = np.arange(M).reshape((N, N))

for i in range(N):

for j in range(N):

data[i,j] = i**j

return(data[2])

%time powers_array_cy(15,225)

CPU times: user 151 µs, sys: 123 µs, total: 274 µs

Wall time: 268 µs

array([ 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256,

512, 1024, 2048, 4096, 8192, 16384])

Note that for a small array like this, the speed up is not significant, you may even have got a slow down, why? Have a think as we go through the final main step on how to speed up code.

For larger problems with larger arrays, speeding up code using cnp arrays are recommended!

Compiler directives

These affect the code in a way to get the compiler to ignore things that it would usually look out for. There are plenty of examples as discussed in the Cython documentation, however the main ones we will use here are;

boundscheck- If set toFalse, Cython is free to assume that indexing operations in the code will not cause any IndexErrors to be raisedwraparound- If set toFalse, Cython is allowed to neither check for nor correctly handle negative indices. This can cause data corruption or segmentation faults if mishandled, so use with caution!

You should implement these at a point where you know that the code is working efficiently and that any issues what could be raised by the compiler are sorted. There are a few ways to implement them;

- With a header comment at the top of a

.pyxfile, which must appear before any code

# cython: boundscheck=False

- Passing a directive on the command line using the -X switch

$ cython -X boundscheck=True ...

- Or locally for specific functions, for which you first need the cython module imported

cimport cython

@cython boundscheck(False)

Let’s see how this applies in our powers example.

import numpy as np # Normal NumPy import

cimport numpy as cnp # Import for NumPY C-API

cimport cython

@cython.boundscheck(False) # turns off

@cython.wraparound(False)

def powers_array_cy(int N, int power): # number of

cdef cnp.ndarray[cnp.int_t, ndim=2] arr

cdef int M

M = N*N

arr = np.arange(M).reshape((N, N))

for i in range(N):

for j in range(N):

arr[i,j] = i**j

return(arr[power]) # returns the ascending powers

%time powers_array_cy(15,4)

CPU times: user 166 µs, sys: 80 µs, total: 246 µs

Wall time: 238 µs

array([ 1, 4, 16, 64, 256, 1024,

4096, 16384, 65536, 262144, 1048576, 4194304,

16777216, 67108864, 268435456])

Typing and Profiling

For anyone new to Cython and the concept of declaring types, there is a tendency to ‘type’ everything in sight. This reduces readability and flexibility and in certain situations, even slow things down in some circumstances, such as what we saw in the previous code block. We have unnecessary typing

It is also possible to kill performance by forgetting to ‘type’ a critical loop variable. Tools we can use are profiling and annotation.

Profiling is the first step of any optimisation effort and can tell you where the time is being spent. Cython’s annotation can tell you why your code is taking so long.

Using the -a switch in cell magics (%%cython -a), or cython -a cython_module.pyx from the terminal creates a HTML

report of Cython and generated C code. Alternatively, pass the annotate=True parameter to cythonize() in the

setup.py file (Note, you may have to delete the C file and compile again to produce the HTML report).

This HTML report will colour lines according to typeness. White lines translate to pure C (fast as normal C code).

Yellow lines are those that require the Python C-API. Lines with a + are translated to C code and can be viewed by

clicking on it.

By default, Cython code does not show up in profile produced by cProfile. In Jupyter notebook or indeed a source file, profiling can be enabled by including in the first line;

# cython: profile=True

Alternatively, if you want to do it on a function by function basis, you can exclude a specific function while profiling code.

# cython: profile=True

import cython

@cython.profile(False)

cdef func():

Or alternatively, you only need to profile a highlighted function

# cython: profile=False

import cython

@cython.profile(True)

cdef func():

To run the profile in Jupyter, we can use the cell magics %prun func()

Generate a profiling report

Use the methoda described above to profile the Montecarlo code. What lines of the code hint at a Python interaction? Why?

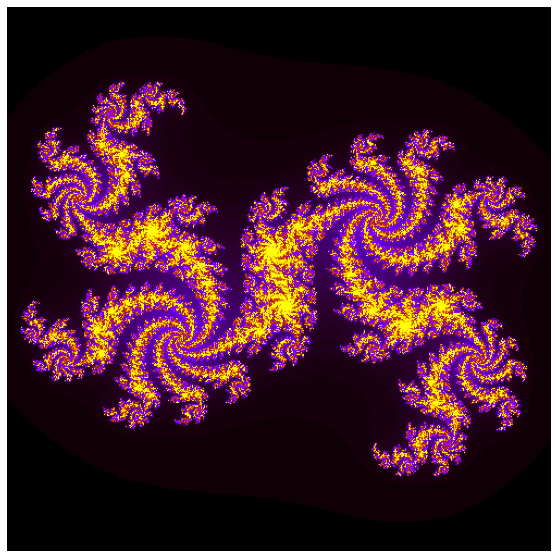

Acceleration Case Study: Julia Set

Now we will look at a more complex example, the Julia set. This is also covered in the Jupyter notebook.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import time

import numpy as np

from numpy import random

%matplotlib inline

mandel_timings = []

def plot_mandel(mandel):

fig=plt.figure(figsize=(10,10))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.set_aspect('equal')

ax.axis('off')

ax.imshow(mandel, cmap='gnuplot')

plt.savefig('mandel.png')

def kernel(zr, zi, cr, ci, radius, num_iters):

count = 0

while ((zr*zr + zi*zi) < (radius*radius)) and count < num_iters:

zr, zi = zr * zr - zi * zi + cr, 2 * zr * zi + ci

count += 1

return count

def compute_mandel_py(cr, ci, N, bound, radius=1000.):

t0 = time.time()

mandel = np.empty((N, N), dtype=int)

grid_x = np.linspace(-bound, bound, N)

for i, x in enumerate(grid_x):

for j, y in enumerate(grid_x):

mandel[i,j] = kernel(x, y, cr, ci, radius, N)

return mandel, time.time() - t0

def python_run():

kwargs = dict(cr=0.3852, ci=-0.2026,

N=500,

bound=1.2)

print("Using pure Python")

mandel_func = compute_mandel_py

mandel_set, runtime = mandel_func(**kwargs)

print("Mandelbrot set generated in {} seconds\n".format(runtime))

plot_mandel(mandel_set)

mandel_timings.append(runtime)

%time python_run()

Using pure Python

Mandelbrot set generated in 22.584877729415894 seconds

CPU times: user 22.5 s, sys: 144 ms, total: 22.7 s

Wall time: 22.7 s

Optimise the Julia set

As mentioned, this pure python code is in need of optimisation. Conduct a step by step process to speed up the code. The steps that you take, as well as the estimated execution times for

N=500should be as follows.

- Compilation with Cython - ~ 19 seconds

- Static type declarations - ~ 0.15 seconds

- Declaration as C function - ~ 0.13 seconds

- Fast Indexing and compiler directives - ~ 0.085 seconds

- use

cimport- look at the loops, is there a faster way of doing it?

As you can see you might expect a speed up of roughly 250-300 times the original python code. The Jupyter notebook outlines the process well if you need it, but try it out yourself. The solution is the final step.

Solution

Feel free to continue experimenting, as you may still find a quicker method!

import numpy as np import time cimport numpy as cnp from cython cimport boundscheck, wraparound @wraparound(False) @boundscheck(False) cdef int kernel(double zr, double zi, double cr, double ci, double radius, int num_iters): cdef int count = 0 while ((zr*zr + zi*zi) < (radius*radius)) and count < num_iters: zr, zi = zr * zr - zi * zi + cr, 2 * zr * zi + ci count += 1 return count def compute_mandel_cyt(cr, ci, N, bound, radius=1000.): t0 = time.time() cdef cnp.ndarray[cnp.int_t, ndim=2] mandel mandel = np.empty((N, N), dtype=int) cdef cnp.ndarray[cnp.double_t, ndim=1] grid_x grid_x = np.linspace(-bound, bound, N) cdef: int i, j double x, y for i in range(N): for j in range(N): x = grid_x[i] y = grid_x[j] mandel[i,j] = kernel(x, y, cr, ci, radius, N) return mandel, time.time() - t0

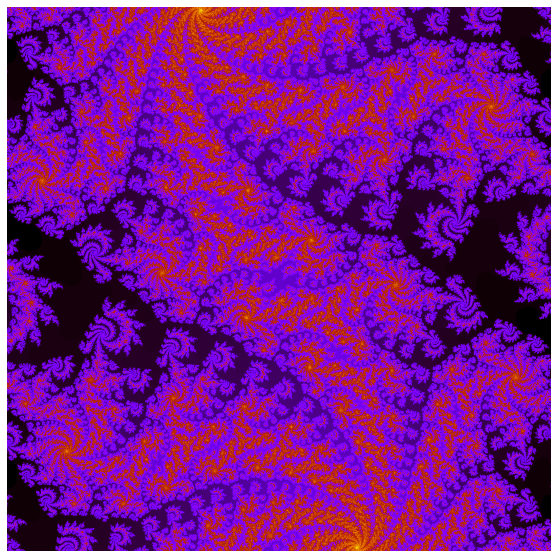

def speed_run():

kwargs = dict(cr=0.3852, ci=-0.2026,

N=2000,

bound=0.12)

mandel_func = compute_mandel_cyt

mandel_set, runtime = mandel_func(**kwargs)

print("Mandelbrot set generated: \n")

print("Using advanced techniques: {}\n".format(runtime))

plot_mandel(mandel_set)

print("Assuming the same speed up factor, our original code would take", (speed_up_factor*runtime)/60, "minutes")

speed_run()

Mandelbrot set generated:

Using advanced techniques: 9.067986965179443

Assuming the same speed up factor, our original code would take 39.29461018244425 minutes

Optimising Cython from scratch

Head to the Jupyter notebook and scroll to Additional Exercises. Look at the cProfile and see if you can improve the performance for the

heat_equation_simple.pyfile.The file can be executed using;

$ python heat_equation_simple.py bottle.datThere are two input files. Running the python file with

bottle.datwill take ~20 seconds. The larger file,bottle_large.datwill take ~10 minutes. Your target will be to bring the execution times ofbottle.datandbottle_large.datto < 0.1 second and < 5 seconds respectively.Solution

The solution can be found in the Jupyter notebook here

Key Points

Cython IS Python, only with C datatypes

Working from the terminal, a

.pyx,main.pyandsetup.pyfile are required.From the terminal the code can be run with

python setup.py build_ext --inplaceCython ‘typeness’ can be done using the

%%cython -acell magic, where the yellow tint is coloured according to typeness.Main methods of improving Cython speedup include static type declarations, declaration of functions with

cdef, usingcimportand utilising fast index of C-numpy arrays and types.Compiler directives can be used to turn off certain python features.